Introductory Note

Dear Mr. Fulton,

As you know, uncovering records related to enslaved people’s lives is a difficult task for several reasons. First and foremost, enslaved people were legally prohibited from learning to read and write. As a result, enslavers authored the vast majority of records on which enslaved people are referenced. Locating records of enslaved ancestors’ lives thus typically requires knowing, at the very least, the identity or identities of their enslaver(s).

Using a combination of census records and death certificates, I was able to trace your paternal ancestors back five generations to your third great-grandfather, Julius Fulton, who was born between 1835 and 1842 and passed away in 1911. Unfortunately, however, I did not uncover any post-Emancipation records identifying Julius Fulton’s former enslaver(s) by name. For this reason, I decided to make an educated guess and see where it led me. I decided, that is, to investigate whether any white persons with the surname “Fulton” resided in or around Williamsburg County, SC in the eighteenth and/or nineteenth centuries: a line of inquiry inspired by a hunch that your ancestors may have adopted their enslavers’ surname as their own.

For the record, this particular hypothesis—that the surname of a formerly enslaved person would match his former enslaver’s—is not one I make often. Contrary to a common misconception, my research demonstrates that many if not most enslaved persons who claimed a surname did not claim the same surname as their enslavers. Likewise, while some formerly enslaved people chose to adopt their former enslavers’ surnames after the Civil War, many chose differently.

Even so, I thought it likely that Julius Fulton would have shared a surname with his former enslaver for a very simple reason, which is that according to my research (fully analyzed in my forthcoming book), individuals enslaved in the antebellum Lowcountry were far more likely to share a surname with their enslaver at any given moment than individuals enslaved elsewhere in the United States. Likewise, African Americans in the Lowcountry were more likely to adopt their former enslaver’s name as their own at Emancipation than African Americans in other regions of the country, especially those residing in the Chesapeake.

Ultimately, this hypothesis was confirmed by a careful review of the Fulton Family Papers housed at the South Carolina Historical Society in Charleston, a collection of wills, property records, and legal documents created by and/or relating to the “white” (Scots-Irish) Fultons of Williamsburg, SC. Of particular interest were various inventories drafted between 1747 and the 1850s, each of which can be viewed through this site’s archive.

What follows is a summary of information gleaned from these records and dozens others which I uncovered in the course of this project. In order to contextualize this information, I have also drawn on the broader research which I have conducted over the past decade. It is my great hope that this site will be of use to you and your family as you seek to know, honor and remember your ancestors.

With gratitude,

Jennie K. Williams, Ph.D.

May 26, 2025

Research Summary

Prior to the eighteenth century, the land now known as Williamsburg, SC was inhabited by several Native American tribes, including the Wee Nee and Pee Dee. Beginning in the early 1730s, however, a wave of European settler-colonialists laid claim to the most fertile land in the area, situated along the Black and Pee Dee Rivers. A 1737 census of the newly-formed Williamsburg Township lists more than a hundred “heads of families,” including David Fulton, the first in a long line of Scots-Irish Fultons in the area.

According to William Willis Boddie’s 1923 History of Williamsburg, the first “African slave in the Township” was a man named “Dick,” supposedly “imported” by Roger Gordon in 1736. If so, David Fulton was not far behind Gordon in acquiring human “property.” A 1746 inventory of Fulton’s estate lists nine enslaved persons, including Jeffree, Mingo, Ceasr, and Cato, all listed as “negro men;” Jeffree, Hector, and Abraham, identified as “negro boys;” Venus, described as a “negro girl';” and one unnamed woman and her infant child, also unnamed.

In all probability, these individuals—and certainly the vast majority of captive Africans brought to Williamsburg in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries—disembarked at the port of Charleston following horrific journeys from West Africa. Indeed, nearly 40% of the entire African population trafficked to North America in the transatlantic slave trade disembarked in Charleston. The largest number (40%) came from Angola, Senegambia (19.5%), the Windward Coast (16.3%), or the Gold Coast (13.3%).

The first generations of Fulton ancestors enslaved in North America likely toiled on South Carolina’s early indigo and rice plantations, including those responsible for much of Williamsburg’s economy in the eighteenth century. Indeed, rice and indigo plantations, both of which thrived in the Lowcountry’s warm, swampy climate, were veritable economic powerhouses, producing lucrative cash crops for European markets. Both crops were extremely labor-intensive to cultivate, especially in South Carolina’s harsh environment. Enslaved Africans endured hours of backbreaking labor, exposure to New World diseases to which they had limited or no immunity, and constant threats of violence.

Despite these and other hardships, enslaved people in South Carolina comprised a majority of the colony’s population by 1708. As a result, South Carolina’s enslaved families and communities, particularly in the Lowcountry, were often especially close-knit. They were also frequently characterized by a greater degree of African cultural retention (in food, music, religion, etc.) than enslaved communities found elsewhere in North America.

In the early 19th century, cotton cultivation surged in Williamsburg County, South Carolina, transforming its agricultural landscape and economic foundation. As the global demand for cotton skyrocketed with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, planters in Williamsburg turned to cotton as a lucrative cash crop, complementing their existing production of rice and indigo. The region’s fertile soils and warm climate proved ideal for cotton farming, and enslaved labor became integral to this booming economy. Plantations expanded rapidly, and cotton exports brought newfound wealth to many white landowners.

Enslaved people on cotton plantations in Williamsburg County and across the South endured grueling labor and harsh conditions, with their lives defined by relentless toil and the constant threat of violence. Typically working in the “gang system” of labor from dawn until dusk, enslaved people spent much of their time in the fields, planting, weeding, and picking cotton under the watchful eyes of overseers who enforced quotas with whips and intimidation. Their days were filled with backbreaking work and little rest, and their nights often brought only a few precious hours of sleep in overcrowded cabins.

“Williamsburg District on May 1, 1860, was the most Southern of all the South. Every man was a cotton planter. Several were physicians, a half dozen were merchants, two or three were lawyers, but every one owned and operated a plantation by virtue of African slave labor. There were practically no ‘poor whites’ in the district. All of this breed had gone away into the far West and become militant abolitionists. Williamsburg then placed its trust in cotton and believed that it was king of the earth.”

— William Boddie, History of Williamsburg, 1923.

At its core, slavery relied upon the conversion of human beings to commodities. Enslavers knew, after all, that property’s every value lies in its ability to come unattached. For this reason, for enslaved people, including Fulton ancestors, kinship was never something that could be passively possessed. It was, instead, an identity and practice that had to be actively and insurgently claimed. Kinship, in other words, was resistance.

Surviving records reveal two clear ways in which the Fulton ancestors fought for and honored kinship. First, Fulton ancestors clearly used intergenerational naming practices to honor loved ones. Numerous names—Benjamin, Joseph, Charlotte, Samuel, John, Mary, Anthony, and others—appear in virtually every generation of the Fulton family, from ancestors enslaved in the eighteenth century all the way to the present. This is all the more remarkable if we consider enslavers’ efforts to influence or even outright control enslaved people’s naming practices. Second, Fulton ancestors formed long-lasting relationships with enslaved people from neighboring plantations. Indeed, for those ancestors seeking romantic life partners, this may well have been a necessity, since many if not most enslaved people on the Fulton plantation were likely related to one another. To see each other, enslaved couples commonly met along waterways or under the cover of forests. The map below suggests this was likely true for Fulton ancestors, including Julius Fulton (1843-1911), who married Henrietta Gamble; the Gamble plantations are represented by blue dots on the map below, while the red dot represents the Fulton property.

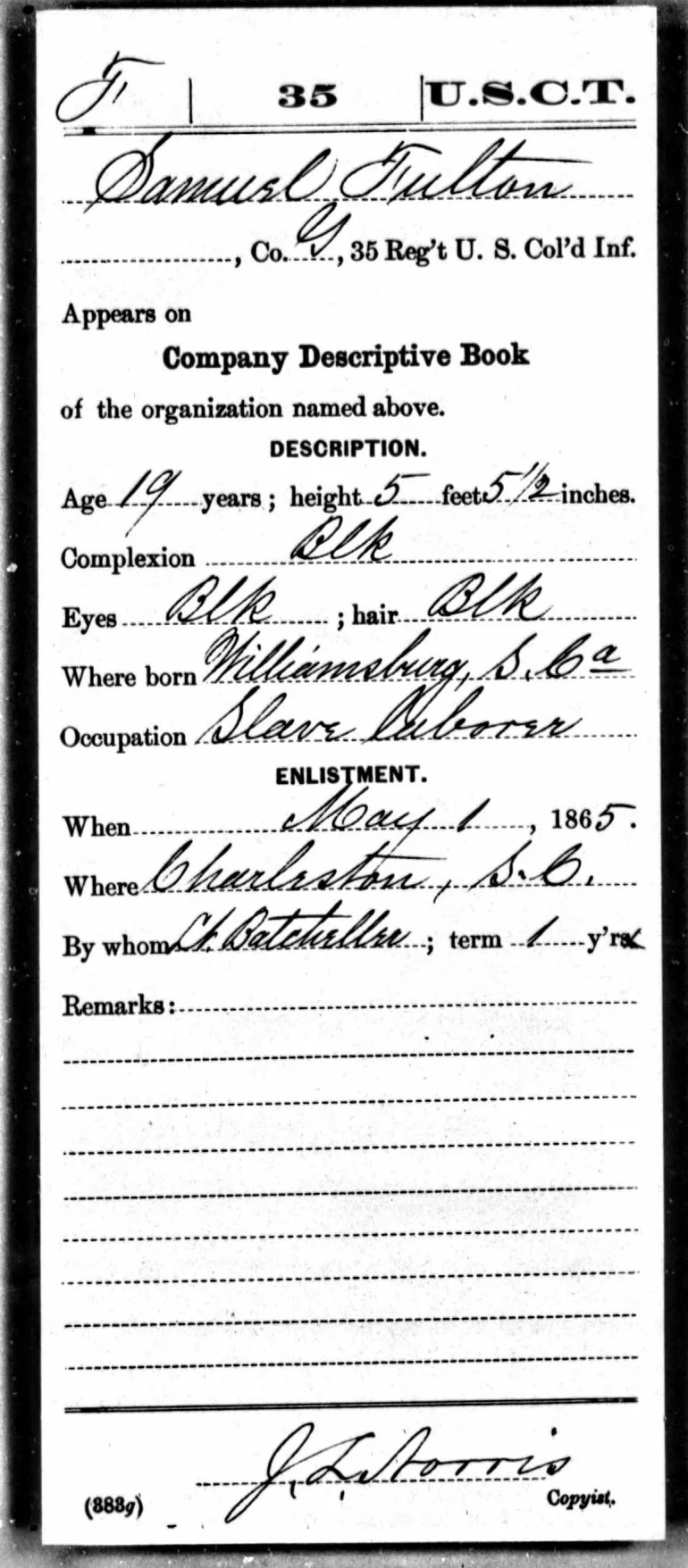

During the Civil War, Williamsburg County, South Carolina, was deeply impacted by the conflict that tore the nation apart. As a predominantly agricultural region dependent on enslaved labor, Williamsburg was strongly aligned with the Confederacy, and many of its white men, including the white Fultons, enlisted to fight in the Confederate Army. The war brought widespread disruption and hardship to the area; Union troops raided hundreds of farms and plantations, destroying crops and property. Meanwhile, enslaved people—including at least one Fulton ancestor, Samuel Fulton (born about 1846)—seized the chance to escape bondage by fleeing to Union lines, where they found opportunities to fight for their own freedom. As Union forces moved through the state, they encountered fugitive slaves who eagerly enlisted in the Union Army, determined to join the cause that promised liberty and justice. These men enlisted in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments and played vital roles in the fight to preserve the Union and end slavery. Their enlistment not only contributed to Union military strength but also symbolized a powerful claim to citizenship and equality, as these soldiers took up arms to secure their rights and help end the brutal institution of slavery that had defined their lives.

After the Civil War, most Fulton ancestors remained in Williamsburg area and worked as farmers. The majority were “general farmers,” meaning their farms had a variety of rotational crops. Most of their income, however, derived from cultivating tobacco.

The years after the Civil War—Reconstruction and the subsequent Jim Crow era—were marked by profound violence and racial terror in South Carolina and throughout the South, as white supremacists sought to reassert their dominance in the aftermath of the Civil War. During Reconstruction, newly freed African Americans exercised their right to vote and held political office, fostering a brief but hopeful period of progress and democratic participation. In response, groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Red Shirts waged campaigns of intimidation, beatings, and murder to suppress Black political power and restore white control. As federal troops withdrew and Reconstruction ended, the violence escalated, laying the foundation for Jim Crow segregation laws that would codify racial inequality for decades. These laws and the accompanying terror—lynchings, race riots, and daily acts of brutality—aimed to strip Black South Carolinians of their civil rights and political rights as citizens.

Fulton ancestors certainly experienced these horrors firsthand. In 1869, for example, Benjamin Fulton—likely a brother or cousin of Julius Fulton (1842-1911)—was killed when he was struck by a railroad car. Official records of this event, including the mortality census pictured below, provide no explanation for this event. Oral history among members of the Fulton Family, however, suggests that Benjamin Fulton was pushed in front of an incoming train by white people—likely members of the Klu Klux Klan—who were angered by his economic success.

And yet, even as newly-freed citizens, Fulton ancestors managed to thrive and prosper. In fact, judging by how frequently the Fultons were written up in local newspapers, the family was quite prominent in the African American community of the area. Fulton men delivered orations, commencement addresses, and sermons. Fulton women, meanwhile, hosted luncheons, read about their weddings in the local paper, and won awards. The May 23, 1907 edition of The County Record (Kingstree’s most prominent African American newspaper) for example, praises an “eloquent and edifying discourse” delivered by the Reverend D. M. Fulton at the Kingstree Graded School’s Commencement. Elsewhere on the same page, Miss Alida Fulton is recognized as the winner of an award for her essay, “The Ideal Woman.”